Harry Truman - Vietnamization

Search and Destroy missions were a crucial part of the American war strategy in Vietnam.

State Department officials in Asia warned Harry Truman, who became president in 1945 upon Roosevelt’s death, that French rule of Vietnam would lead to “bloodshed and unrest.” But Truman did not share his predecessor’s anti-colonialism and ultimately acquiesced to the reestablishment of France’s prewar empire, which he hoped would shore up France’s economy and national pride.

State Department officials in Asia warned Harry Truman, who became president in 1945 upon Roosevelt’s death, that French rule of Vietnam would lead to “bloodshed and unrest.” But Truman did not share his predecessor’s anti-colonialism and ultimately acquiesced to the reestablishment of France’s prewar empire, which he hoped would shore up France’s economy and national pride.

No sooner did the French arrive back in Vietnam, with the guns of World War II barely gone cold, than fighting broke out against Ho’s Viet Minh forces. At first, the United States remained officially neutral, even as it avoided any contact with Ho. In 1947, however, Truman asserted that U.S. foreign policy was to assist any country whose stability is threatened by communism. Then the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, plus the flow of aid from China and the Soviet Union to the Viet Minh, prompted Truman to reexamine Vietnam in a Cold War light.

Fearing that Vietnam, too, would become a communist state, he sent over transport planes and jeeps, along with 35 military advisers, as part of a multimillion-dollar aid package.

U.S. involvement in the conflict would only deepen from there. By the end of Truman’s presidency, the United States was funding more than one-third of France’s war costs, a number that would soon skyrocket to about 80 percent.

Dwight D. Eisenhower - Vietnam War Timeline

Whether they volunteered or were drafted, 1 out of 10 soldiers were injured or killed during Vietnam.

In 1954, the French suffered a catastrophic defeat at Dien Bien Phu, bringing their colonial reign to an end. Some U.S. officials had pushed for air strikes, including the possible use of nuclear weapons, to save the French position. But Dwight D. Eisenhower, who succeeded Truman, demurred, refusing to involve the United States in another major conflict so soon after the Korean War.

In 1954, the French suffered a catastrophic defeat at Dien Bien Phu, bringing their colonial reign to an end. Some U.S. officials had pushed for air strikes, including the possible use of nuclear weapons, to save the French position. But Dwight D. Eisenhower, who succeeded Truman, demurred, refusing to involve the United States in another major conflict so soon after the Korean War.

“I am convinced that no military victory is possible in that kind of theater,” the president wrote in his diary.

Yet because Eisenhower subscribed to the “domino theory,” which held that if one country fell to communism then its neighbors would follow, he refused to abandon Vietnam altogether.

The nation was partitioned in two, with Ho in control of the North and pro-Western leader Ngo Dinh Diem in control of the South. Elections were supposed to take place to reunite Vietnam, but Diem, with U.S. support, backed out for fear that Ho would win.

Though Diem proved corrupt and authoritarian, Eisenhower called him “the greatest of statesmen” and “an example for people everywhere who hate tyranny and love freedom.” More importantly, he also supplied Diem with money and weapons, sending nearly $2 billion in aid from 1955 to 1960 and increasing the number of military advisors to around 1,000.

By the time Eisenhower left office, open fighting had broken out between Diem’s forces and the so-called Viet Cong, communist insurgents in the South who were backed by North Vietnam. Each side employed brutal tactics, including torture and political assassinations.

The Vietnam War was now in full swing, and the United States was right in the middle of it.

John F. Kennedy

John F. Kennedy's progressive agenda during the 1960s inspired a new generation of optimism in America.

After visiting Vietnam as a congressman in 1951, John F. Kennedy publicly lambasted U.S. efforts to assist the French, saying that to act “in defiance of innately nationalistic aims spells foredoomed failure.” Three years later, he presciently declared, “I am frankly of the belief that no amount of American military assistance … can conquer an enemy which is everywhere and at the same time nowhere.”

After visiting Vietnam as a congressman in 1951, John F. Kennedy publicly lambasted U.S. efforts to assist the French, saying that to act “in defiance of innately nationalistic aims spells foredoomed failure.” Three years later, he presciently declared, “I am frankly of the belief that no amount of American military assistance … can conquer an enemy which is everywhere and at the same time nowhere.”

His tune changed, however, by the time he ran for president in 1960, in part over concerns he would be called soft on communism. Once in the White House, Kennedy provided South Vietnam with jet fighters, helicopters, armored personnel carriers, river patrol boats and other tools of war. He also authorized the use of napalm, as well as defoliants such as Agent Orange.

Meanwhile, under his watch, the number of military advisers rose to about 16,000, some of whom began engaging in clandestine combat operations. Originally a supporter of Diem, Kennedy sanctioned a coup in 1963 that resulted in Diem’s death just weeks prior to his own assassination.

Near the end of his life, JFK hinted to aides that he might withdraw from Vietnam following his re-election, but it’s unclear whether he would have actually done so.

Lyndon B. Johnson

Why Did Columbia University Students Protest in 1968?

Learn how the Vietnam War and the construction of a gym on campus prompted Columbia University student groups to protest the administration in 1968. See how their numbers swelled into the thousands and inspired student protests all over the country.

At the time of Kennedy’s assassination, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War remained fairly limited. But that changed in August 1964, when the so-called Gulf of Tonkin incident prompted Congress to grant expansive war-making powers to newly installed President Lyndon B. Johnson.

At the time of Kennedy’s assassination, U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War remained fairly limited. But that changed in August 1964, when the so-called Gulf of Tonkin incident prompted Congress to grant expansive war-making powers to newly installed President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Recognizing that the South Vietnamese government and army were on the verge of collapse, Johnson sent the first U.S. combat troops into battle in early 1965. He simultaneously authorized a massive bombing campaign, codenamed Operation Rolling Thunder, that would continue unabated for years.

Draft calls soon skyrocketed—along with draft resistance—and by 1967 there were around 500,000 U.S. troops in Vietnam. That same year, large anti-war demonstrations popped up in cities across America.

U.S. officials kept insisting that victory was imminent. But, as the Pentagon Papers would later reveal, these comments were deeply misleading. In reality, the conflict had devolved into a quagmire.

Vietnam became so polarizing, and Johnson’s name became so synonymous with the war effort, that he ultimately decided not to run for re-election in 1968.

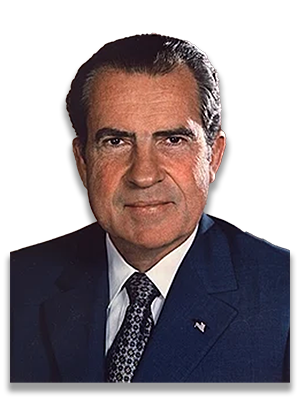

Richard Nixon campaigned for the White House promising to end the Vietnam War. It later emerged, however, that he had secretly tried to sabotage peace talks in order to improve his electoral chances.

Richard Nixon campaigned for the White House promising to end the Vietnam War. It later emerged, however, that he had secretly tried to sabotage peace talks in order to improve his electoral chances.

As president, Nixon gradually withdrew American troops as part of his policy of “Vietnamization.” Yet he escalated the conflict in other ways, approving secret bombing raids of neighboring Cambodia in 1969, sending ground troops into Cambodia in 1970 and sanctioning a similar invasion of Laos in 1971, all in a largely futile mps.

Nixon also ordered the most intense air assault of the war, pummeling North Vietnamese cities with roughly 36,000 tons of bombs late in 1972.

In January 1973, just as the Watergate scandal was heating up, Nixon finally ended direct U.S. involvement in Vietnam, saying “peace with honor” had been achieved. As it turned out, though, fighting continued until 1975, when North Vietnamese troops marched into Saigon, South Vietnam’s capital, and reunified the nation under communist rule.

![]()

![]()

VSPA is an association for USAF Vietnam War Veterans who served in Vietnam or Thailand from 1960-1975, as Air Police / Security Police or as an Augmentee. Visit the main pages for information on joining

Please feel free to copy photos or stories. Just give the author/photographer, & VSPA a credit line.