Nose Art

For centuries warriors have adorned their weapons….

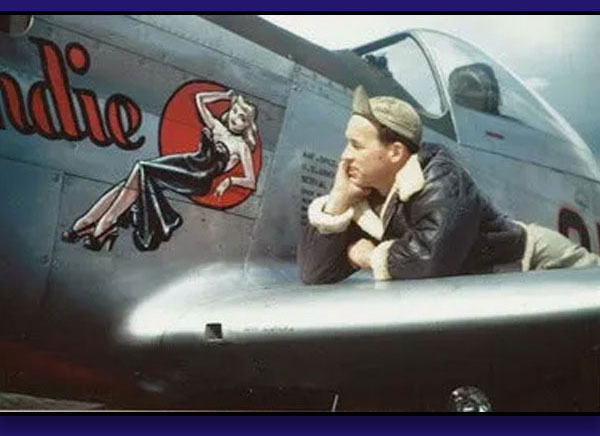

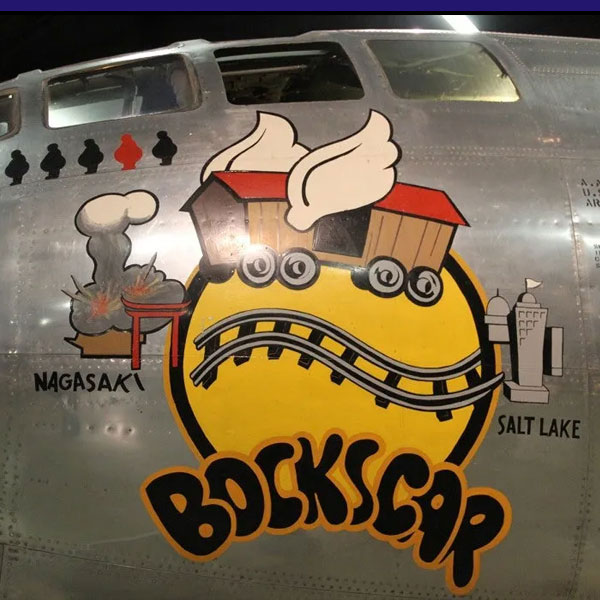

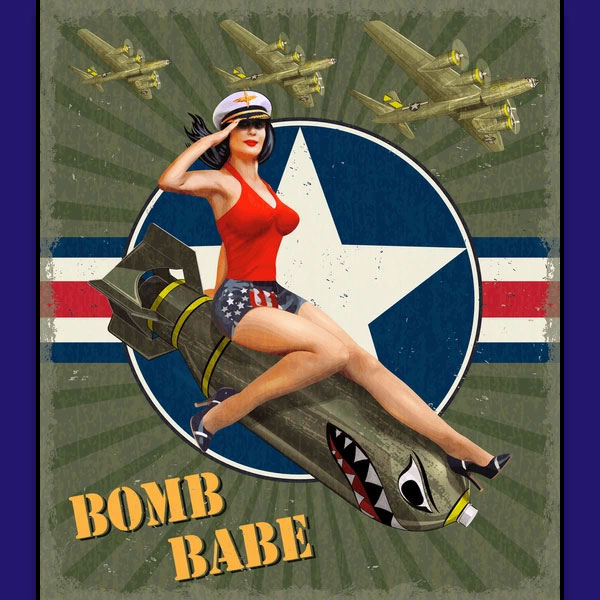

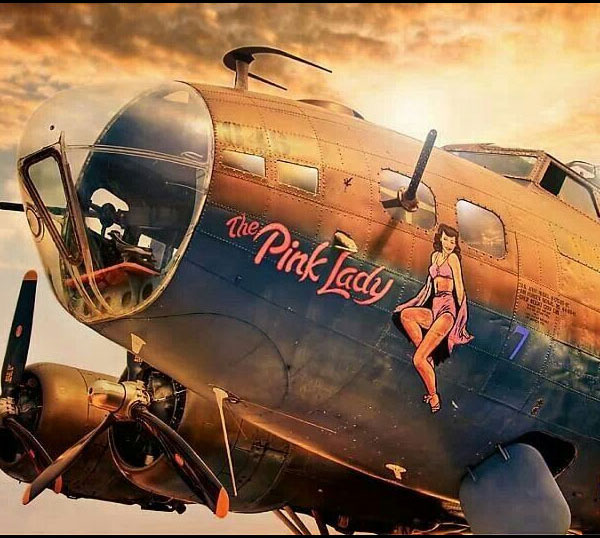

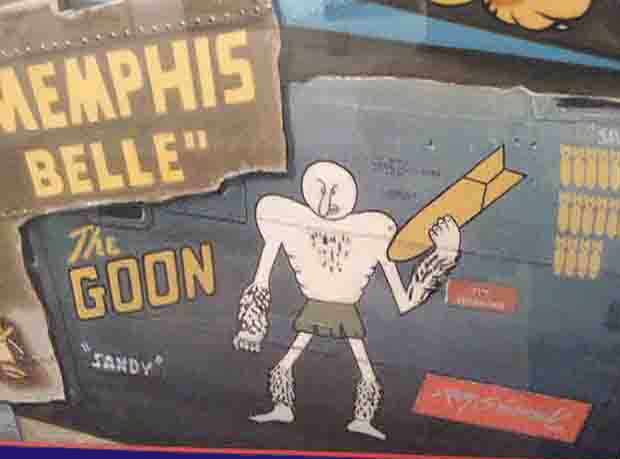

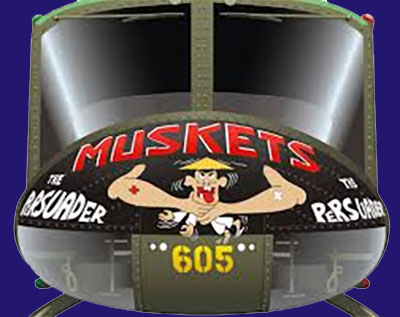

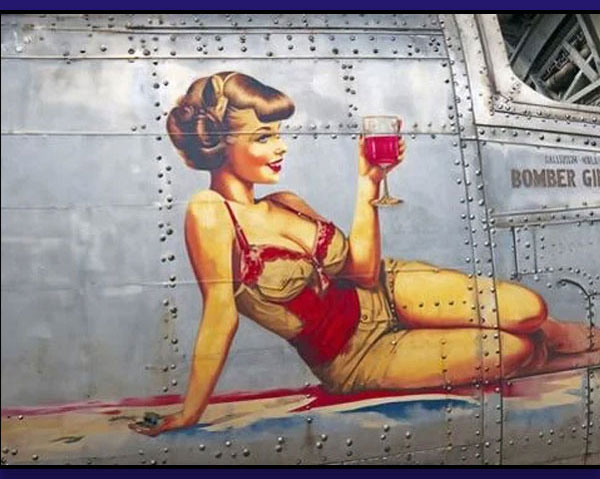

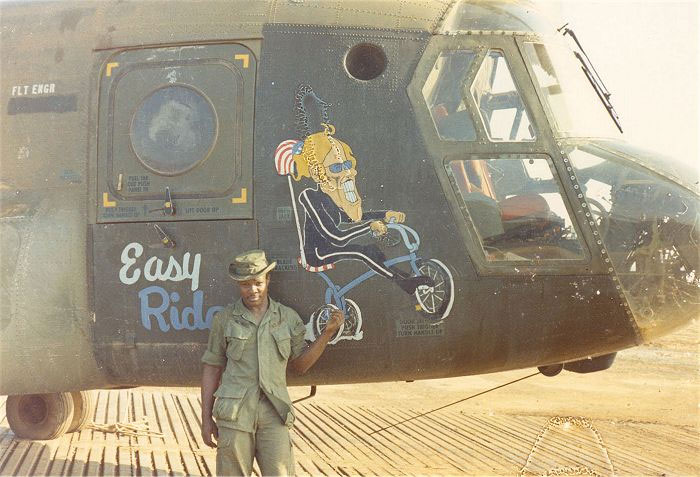

The Wild History of Military Plane Paintings For centuries warriors have adorned their weapons, shields, and accouterments with symbols, shapes, or figures representing their individuality and/or a collective belonging. These colorful depictions often reflected a sense of pride, association, or expression of martial spirit. The tradition continued into the 20th century, with the advent of military aviation allowing for such expressions on an even larger canvas.

The Wild History of Military Plane Paintings For centuries warriors have adorned their weapons, shields, and accouterments with symbols, shapes, or figures representing their individuality and/or a collective belonging. These colorful depictions often reflected a sense of pride, association, or expression of martial spirit. The tradition continued into the 20th century, with the advent of military aviation allowing for such expressions on an even larger canvas.